A booming pandemic recovery has buoyed rural counties that historically lagged behind national economic and population growth. But though these gains occurred under a Democratic administration, they are unlikely to swing red states to blue in November, a recent analysis from the Economic Innovation Group found. The Daily Yonder shares the key details and insights.

The economic analysis looked at just under 1,000 counties that experienced lagging population and income growth between 2000-2016. Approximately 90% of the counties examined in the analysis were categorized as rural. While EIG draws from the same Office of Management and Budget classification of "rural" as the Daily Yonder, EIG makes several distinctions: Rural counties as defined by EIG include all non-metropolitan counties with a population less than 50,000 and any county not categorized as urban or exurban/suburban.

EIG calls these counties "left behind" counties, a framework that does not necessarily account for their full economic and cultural diversity.

"We wanted to draw attention to the fact that these places are not growing at the same rate as the rest of the country," said August Benzow, author of the study.

In the run-up to the November presidential election, the analysis, which examined data from 2000-2023, aimed to provide insight into how historically lagging counties have changed since the 2016 and 2020 election cycles.

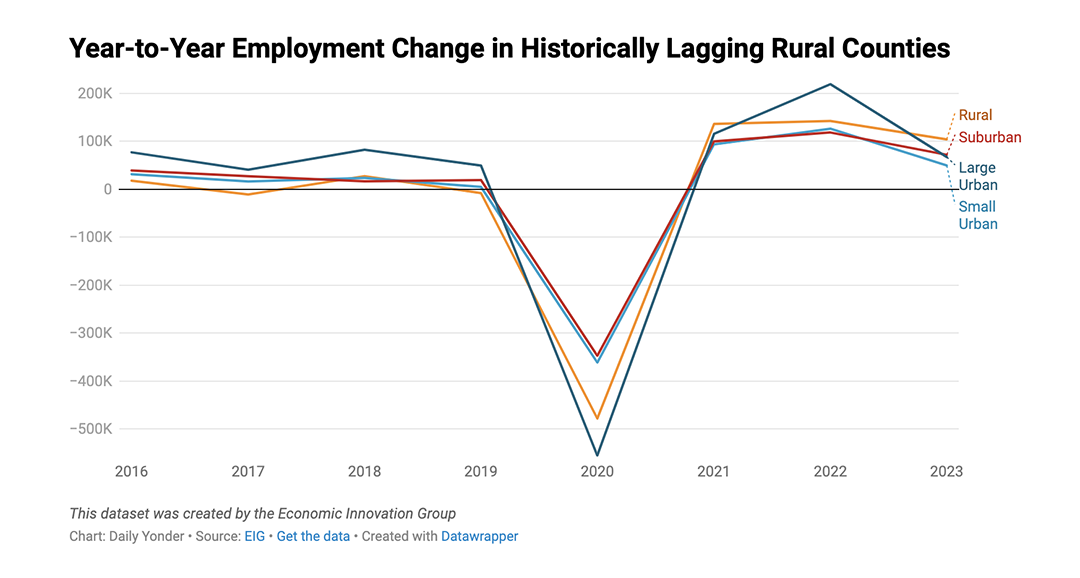

As the United States continues to recover from the recession wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, the rural counties that EIG analyzed did better than urban counties. This finding is different from what the Daily Yonder has tracked with regard to rural versus urban counties as a whole.

When asked how historically lagging rural counties compare to rural counties as a whole, Benzow said that the historically lagging rural counties in the EIG analysis are doing slightly better than other lagging counties included in the analysis.

"We're not saying they're doing better than all non-rural counties," he said. As a whole, rural counties are behind metropolitan counties with regard to change in employment. But the specific subset of rural counties included in Benzow's analysis demonstrates a small departure from the overall trend.

Benzow said that among the historically lagging counties EIG analyzed, rural and urban counties experienced the economic impacts of the pandemic differently.

"The economic impacts are much more strongly felt in [historically lagging] urban counties, where you had more things like lockdowns and business closing and people moving out of urban spaces," Benzow told the Daily Yonder.

For historically lagging rural counties, these trends offered opportunity. Benzow said the rural communities EIG included in the analysis were able to bounce back more quickly from the pandemic because they did not experience the same amount of depopulation or business closure as their urban counterparts. In some cases, the rural counties in the EIG analysis capitalized on the migration of people out of high-density areas.

Of the counties included in the analysis, the rural ones are the closest to regaining pre-COVID-19 employment levels. In 2023 alone, the historically lagging rural counties that were analyzed added 104,000 jobs. This represents significant growth over the 10,000 jobs that were being added each year in those counties in the three years before the pandemic.

Still, the analysis notes that there are fewer workers employed in historically lagging counties today than there were almost 25 years ago. In the counties analyzed, there were 1.8 million fewer jobs in 2023 than in 2000, a statistic indicative of the struggle these historically lagging counties face compared to the rest of the country. Much of this struggle is rooted in the loss of manufacturing jobs during the early 2000s and during the Great Recession.

During this time and the decade that followed, Benzow said there were few policies in place to protect these counties from job and population loss. It was also during this time that many historically lagging counties began to shift their support more strongly in favor of Republican candidates during presidential elections. Between 2008 and 2016, support for GOP candidates gained 16 percentage points in the counties analyzed, with 83% of voters casting their ballots for the Republican ticket in 2020.

Now, in the wake of the pandemic recession, Benzow said the situation in these counties looks different than it did in the 2010s.

"These are places that have a lot of economic potential that has not been tapped into," Benzow said.

A return to what Benzow calls "place-based policies"—federal policies that direct investment toward specific areas—can provide a mechanism for closing the economic gap between the counties analyzed and the rest of the country. At a federal level, it is too early to tell how recent policies like the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 will play out in historically lagging counties. Any of its economic effects will not be felt for a few years as new projects and employment opportunities are still getting off the ground.

Although this post-pandemic economic boom has taken place during a Democratic administration, Benzow said it is unlikely to sway voters in historically lagging counties to support a blue ticket in November. The economic reality in these counties is still one that trails behind the rest of the country. In 2022, 48% of the counties analyzed in the EIG study recorded median income growth behind the national income growth rate, and in 2023, 80% of these counties were behind the national population growth rate.

"People tend to define their economy based on where they live," said Benzow. "Obviously, every vote is different, and national economic concerns are important as well, but people tend to think of their own communities when they think about how well Congress is doing."

This story was produced by The Daily Yonder and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.